For a modern driver accustomed to mandatory seasonal tire changes, the very idea of driving on summer tires in winter seems almost insane. The first serious snowfall in a major city is enough to paralyze traffic: hundreds of cars are helplessly spinning their wheels, stretching traffic jams for kilometers, and the number of minor collisions rises sharply. Today, winter tires are perceived as an immutable truth — as basic a safety element as seat belts or working brakes.

However, just a few decades ago, the road reality looked completely different. In the USSR, the vast majority of motorists used the same set of tires all year round. The concepts of "studded" or "non-studded" simply did not exist, but at the same time, the roads did not turn into a continuous zone of chaos, and mass accidents were not the norm. This seeming paradox is explained not by any one secret, but by a whole set of factors — from the peculiarities of technology and roads to the driving culture and even the composition of the rubber. To understand how it worked, it is important to discard modern ideas and look at the situation through the eyes of a driver of that era, whose experience was radically different from today's.

Car and Road: Different Technology and a Different Environment

First of all, the cars themselves and the conditions in which they were operated were fundamentally different. Soviet passenger cars — "Zhiguli", "Moskvich", "Volga" — had modest dynamic capabilities. Their engines were not highly powerful, and acceleration was unhurried. The car physically did not allow you to suddenly take off or enter a turn at high speed, which automatically reduced the likelihood of skidding on a slippery surface.

The weight distribution of such cars was more even, and the steering was heavy and full of feedback. The driver literally felt how the wheels interacted with the road and felt the approach of loss of grip in advance.

An equally important factor was the road network. Outside of major cities, asphalt was rare, and in the cities themselves, winter road maintenance looked different than it does today. Instead of chemical reagents, sand or slag was used. This simple abrasive created stable grip even for hard rubber, especially on packed snow.

But perhaps the main difference was the traffic density. The number of cars on the roads was many times less than today. The driver did not have to constantly maneuver in a tight stream, brake sharply, or change lanes. The distance could be kept with a large margin, and the road often seemed almost empty. It was this space for maneuver and time for reaction that became one of the key elements of safety.

Driving Culture: Caution as the Norm

The Soviet driver thought and acted differently. A car was a rarity and a value that was saved up for years. Losing it in an accident meant not just losing transport, but losing a serious life resource. Therefore, the car was treated with care, and risk was seen as an unacceptable luxury.

Preparation for a winter trip began long before the start. Warming up the engine, thoroughly cleaning the windows, and checking the battery were considered mandatory procedures. The driving itself was based on the principles of smoothness and foresight. Sharp accelerations and braking were under an unspoken ban, and steering wheel turns were performed carefully and in advance.

They often started in second, and sometimes even in third gear, to reduce the torque on the drive wheels and avoid wheelspin. Braking was mainly done by the engine, and the brake pedal was used as carefully as possible. The driver always looked far ahead, slowing down in advance before intersections, climbs, and suspiciously shiny sections of the road.

Recklessness was not encouraged either socially or practically. Experience was passed from older drivers to younger ones, forming a stable culture of respect for the road and technology. Mistakes were costly, so they learned not to make them.

"Soviet All-Season" and Proven Techniques

The absence of the term "winter tires" did not mean complete uniformity of tires. The tires of that time were closer in their properties to modern all-season tires. They were made from softer compounds than today's summer tires and retained their elasticity longer in the cold, although by modern standards they were still considered hard.

The tread was designed primarily for snow and mud — the main winter surfaces outside the city. The deep pattern promoted self-cleaning and allowed confident movement through snow porridge. In the 1980s, the first specialized tire, the "Snowflake," appeared. It was hard and without studs, but it had an aggressive, almost off-road pattern, becoming the first step towards seasonal specialization.

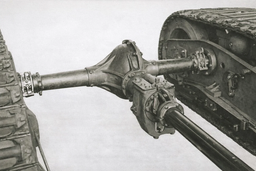

Special mention should be made of snow chains. For many drivers, especially those living outside the city, a set of chains in the trunk was as normal as a jack or a spare tire. In difficult conditions — on climbs or on bare ice — chains were put on the drive wheels and turned a passenger car into something like an all-terrain vehicle. This simple solution effectively compensated for the lack of specialized winter tires.

Infrastructure and Mutual Assistance

The road environment was complemented by a special social atmosphere. There were no strict regulations or mandatory deadlines for changing tires, fines, or total control. Responsibility rested entirely with the driver, which fostered independence and caution.

There was an unspoken rule of mutual assistance on the road. A stuck or skidded car was helped to be pushed out almost without hesitation. This was perceived as the norm, not as an exception. Cleaning roads with sand, not reagents, gave clear guidelines: if there is abrasive under the wheels, there is grip; if there is clean ice, you need to be extremely careful. The simple system worked effectively in conditions of low traffic load.

Why It Worked and Why It Doesn't Work Today

The use of summer tires in winter in Soviet times was made possible by a combination of factors, most of which have disappeared. Weak engines, empty roads, a special culture of smooth driving, chains, and sand instead of reagents formed a unique ecosystem where specialized winter tires were not vital.

It is incorrect to transfer this experience to modern conditions. Today's cars are more powerful, faster, and more complex, and traffic density and driving style leave no room for error. To realize the potential of modern technology, appropriate grip is required, which is provided only by high-quality winter tires.

And yet, the main lesson of the past remains relevant. No tire, even the most perfect one, will replace driving skills. Smoothness, foresight, distance, and a sober assessment of conditions are universal principles of winter driving. Technologies change, but the physics of friction and the laws of inertia remain unchanged, as does the responsibility of the person behind the wheel.