The Olympic motto Citius, Altius, Fortius - "Faster, higher, stronger" - has symbolized the pursuit of progress for decades. In modern automotive engineering, it can be reformulated as: faster, more compact, more efficient. This is how engine building is developing today.

Until recently, the axiom "there is no replacement for displacement" seemed unshakable. A large naturally aspirated engine was associated with reliability, torque reserve, and high dynamics. However, in the 21st century, the situation has changed dramatically: compact turbocharged engines are increasingly surpassing large naturally aspirated units - both in terms of output and efficiency.

The reason for this is not the rejection of physical laws, but a fundamentally different engineering approach based on precise calculations, modern chemistry, and controlled combustion processes.

Historical context: forced induction is not a new invention

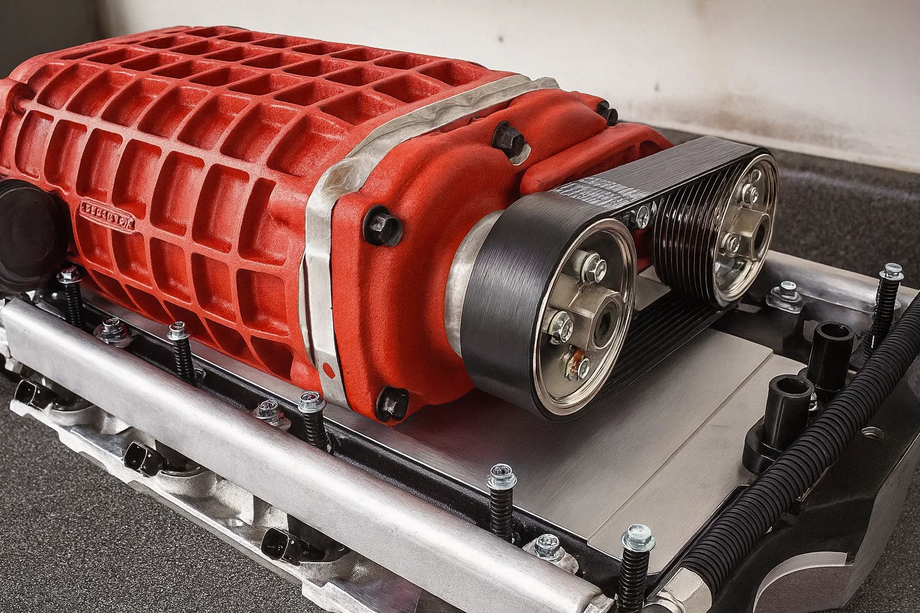

Turbocharging and mechanical superchargers are often perceived as a product of recent decades. In fact, experiments with forced cylinder filling were conducted back in the mid-20th century. In the late 1950s, production cars in the United States were already equipped with compressors - in particular, Studebaker and Ford models.

However, early forced induction systems had serious drawbacks. Mechanical superchargers took some of the engine's power, significantly increased air temperature, and required a reduction in compression ratio. This led to increased fuel consumption, overheating, and reduced service life. As a result, automakers again focused on increasing displacement, postponing the development of forced induction for decades.

The return to the idea of a compact but powerful engine became possible only after a technological breakthrough in fuel systems and thermodynamics.

The role of fuel and direct injection

A key element of modern evolution has been direct fuel injection. Unlike traditional systems, where the air-fuel mixture is formed in the intake tract, modern engines deliver gasoline directly into the combustion chamber under high pressure.

This process has an important effect: when fuel evaporates inside the cylinder, the air charge is intensely cooled. The temperature drops by tens of degrees, which significantly reduces the risk of detonation. Thanks to this, engineers were able to combine high boost with a high compression ratio - previously incompatible parameters.

As a result, modern turbo engines reach compression ratio values characteristic of sports naturally aspirated engines of the past, while maintaining compactness and efficiency.

However, such technologies require increased accuracy in operation. The phenomenon of premature ignition of the mixture at low speeds (LSPI) has become a new engineering problem, which led to the emergence of special motor oils and more stringent maintenance requirements.

Mechanical efficiency and loss reduction

In addition to chemistry and thermodynamics, mechanical efficiency plays an important role. Large engines have more moving parts, a larger friction area, and significant heat losses. A significant part of the energy generated is spent on overcoming its own resistance.

Modern small-displacement engines benefit from lower masses, a reduced number of parts, and more compact combustion chambers. Engineering logic has shifted from "bigger and simpler" to "smaller and more efficient." Increased loads are compensated by precise process control and the use of high-strength materials.

This approach allows you to get high power output, but at the same time reduces the permissible safety margin and increases the engine's sensitivity to operating conditions.

Traction character and subjective perception of dynamics

The changes affected not only the numbers in the specifications, but also the sensations behind the wheel. Naturally aspirated engines of the past developed maximum torque in a narrow rev range, requiring active use of the gearbox.

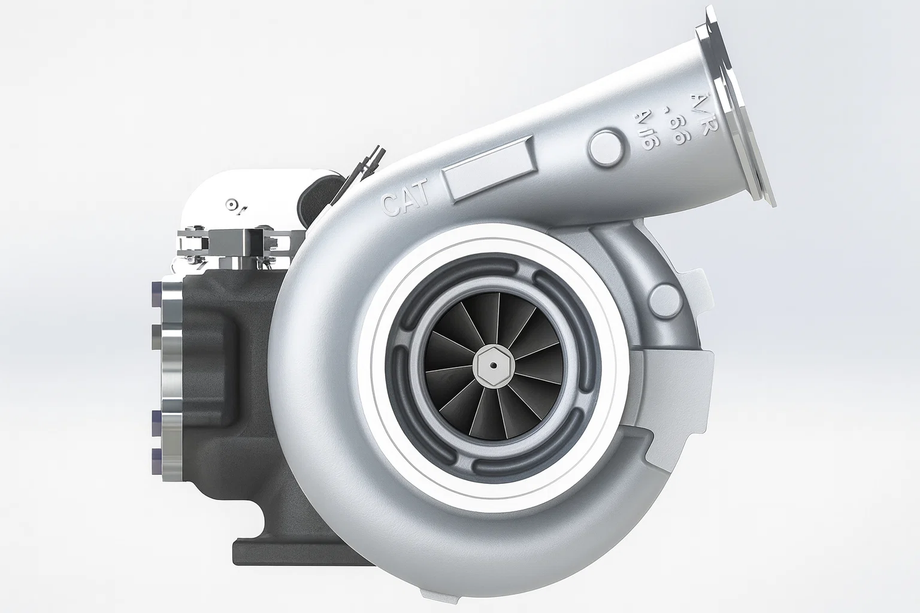

Modern turbo engines, thanks to twin-scroll turbines and variable valve timing systems, form the so-called "torque shelf." Maximum thrust is available from low revs and remains in a wide range, providing confident acceleration without the need for frequent gear changes.

It is the uniformity and availability of thrust that creates a feeling of lightness and high dynamics, even with a relatively small displacement.

Result: efficiency instead of excessive reserve

Modern turbocharged engines have become a logical result of evolution. They provide high dynamics, reduce fuel consumption and reduce the weight of the car. However, this efficiency is achieved at the cost of increased loads and more stringent maintenance requirements.

The safety margin characteristic of engines of past decades has given way to precise calculation and operation at extreme modes. This does not make modern engines worse - but requires a different attitude from the owner.

A turbo engine today is a high-tech tool: efficient, complex and requiring careful operation. This is its strength and its limitation.